|

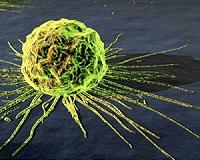

Seattle, Washington (SPX) Apr 5, 2011 A technique Michael Jackson reportedly used to prolong his youth is showing promise as a way to boost the effectiveness of a natural cancer remedy. An environment of pure oxygen at three-and-a-half times normal air pressure adds significantly to the effectiveness of a natural compound already shown to kill cancerous cells, researchers at the University of Washington and Washington State University recently reported in the journal Anticancer Research. The compound artemisinin - isolated from Artemisia annua L, commonly known as wormwood - is a natural remedy widely used to treat malaria. In the mid-1990s UW researchers were the first to explore its ability to treat cancer. In the new study, using artemisinin or high-pressure oxygen alone on a culture of human leukemia cells reduced the cancer cells' growth by 15 percent. Using them in combination reduced the cells' growth by 38 percent, a 50 percent increase in artemisinin's effectiveness. "If you combine high-pressure oxygen with artemisinin you can get a much better curing effect," said author Henry Lai, a UW research professor of bioengineering. "We only measured up to 48 hours. Over longer time periods we expect the synergistic effects to be even more dramatic." The history of artemisinin brings to mind an Indiana Jones story. In the early 1970s, Lai says, Chinese leader Mao Zedong issued an order to develop an anti-malarial treatment. At the same time, a farmer in central China discovered a 2,000-year-old tomb that contained three coffins. One coffin contained a silk scroll describing various prescriptions, including artemisinin to treat malaria. The Chinese followed the directions and thus rediscovered an ancient remedy. Today, artemisinin is widely used in Asia and Africa for malaria treatment. In the decades since, scientists have discovered artemisinin reacts with iron within a cell to form a free radical, a highly reactive charged particle that destroys the cell. Because the malaria parasite is high in iron, artemisinin targets malaria-infected cells. Since rapidly dividing cancer cells also need iron to form new DNA, Lai theorized they would also make targets for artemisinin. Subsequent research showed this to be the case. Lai and colleagues at the UW developed a variant several thousand times more potent than natural artemisinin, which was licensed in 2004 to a Chinese company. "Artemisinin is a promising low-cost cancer treatment because it's specific, it's cheap and you don't have to inject it," Lai said. "It's 100 times more specific than traditional chemotherapy," he added. "In breast cancer, it's even better." Lai says he's long hypothesized that high oxygen levels would enhance artemisinin's effects, because oxygen promotes the formation of free radicals. In 2010, he put the theory to the test in a hyperbaric chamber that co-author Raymond Quock, WSU professor and chair of pharmaceutical sciences, has been using to study highly pressurized oxygen's ability to relieve pain. Hyperbaric chambers, filled with oxygen at high pressure, help scuba divers who surface too quickly gradually readjust to normal oxygen levels. A photo of pop singer Jackson in the mid-80s sleeping in a portable hyperbaric chamber sparked rumors that he was trying to heal scars from plastic surgery, retain his youthful appearance or extend his lifespan. The photo turned out to be a publicity stunt, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved hyperbaric oxygen therapy for several ailments, including decompression sickness, carbon-monoxide poisoning, severe burns and slow-to-heal wounds. In clinical practice, the artemisinin-hyperbaric study could lead to people or animals spending time in a hyperbaric chamber to enhance the artemisinin's effectiveness. Other co-authors are Yusuke Ohgami, Catherine Elstad and Eunhee Chung of WSU and Donald Shirachi of the Chico Hyperbaric Center. The research was funded by the Washington State University College of Pharmacy and the Chico Hyperbaric Center. In related artemisinin work, funded through a $1.5 million grant from the state's Life Sciences Discovery Fund to a team led by UW chemistry professor Tomikazu Sasaki: UW researchers are developing synthetic artemisinin compounds with enhanced potency and anti-cancer selectivity, and WSU researchers are conducting a clinical trial evaluating these compounds' ability to treat cancer in dogs. The molecular-engineered artemisinin compounds, which are stronger and more targeted than natural artemisinin but can still be taken by mouth, are licensed to Artemisia Biomedical of Newcastle, Wash. WSU crop scientists are planting Artemisia annua in eastern Washington to test whether the region could plant artemisinin as a commercial crop. Researchers are working with Northwest Organic Foods, a Washington chicken-feed company, to try adding artemisinin, instead of small amounts of arsenic, to chicken feed. Artemisinin acts as a natural preventative for avian coccidia infection, one of the poultry industry's most costly parasitic diseases.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

Related Links University of Washington Hospital and Medical News at InternDaily.com

Patients Are Willing To Undergo Multiple Tests For New Cancer Treatments

Patients Are Willing To Undergo Multiple Tests For New Cancer TreatmentsScottsdale AZ (SPX) Mar 07, 2011 Cancer patients are willing to undergo many tests to receive advanced experimental treatment in clinical trials, according to a new study by Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale Healthcare and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen). Researchers said patients' willingness to undergo tests bodes well for the future of personalized medicine, in which specific treatments are prescribed depend ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |